In Melbourne, Australia, in the mid-1960s, the subject of Yoga was still a mystery to most people. If they had any concepts about it, these would probably have been stereotypes of weird bodily contortions or “standing on one’s head”.

It was Melbourne film maker John Murray who undertook to dispel some of these misconceptions by making a documentary film about the subject. The film is called “Yoga and the Individual” and it won a Silver Award at the 1966 Australian Film Institute awards.

To provide a visual demonstration of Yoga physical practices, John Murray turned to Vijayadev and Jill Yogendra, Co-Principals of The Yoga Education Centre in Melbourne. They are listed in the film credits as “Yoga practitioners and advisors on ‘Integrated Yoga’”.

When I enrolled in a Yoga course at Monash University in the early 1970s, it was The Yoga Education Centre which provided the teachers and the authoritative guidance in the subject. The film “Yoga and the Individual” was periodically shown to students as an introduction to the subject and its cultural background and as a teaching aid for the Yoga physical practices.

John Murray passed away in 2020. I was fortunate to speak with him about the film in 2019. At that time he was arranging digital scans of his film, with the intention that these be made available online. (see notes below “Addendum #1: History of the Film”)

Since then, with the generous help of his children, Scott, Sue and Shahaan, I have been able to assist in completing some degree of restoration of the film. (see notes below “Addendum #2: Scanning and Restoration”)

Amidst much mis-information that exists about the subject of Yoga, I believe this film provides a well-researched, sincere and authentic introduction to the subject. This almost forgotten documentary deserves to be seen by a new generation of students interested in Yoga.

Further information about the film’s history and restoration is provided below.

Addendum #1: History of the Film

In the 57 years (as of this writing) since the film was made, the perception of Yoga in popular culture has changed. It is both more familiar, but at the same time often promoted by people who do not have a direct connection to the authentic tradition.

Vijayadev Yogendra had been trained by his father, Shri Yogendra, founder in 1918 of the respected Yoga Institute of Bombay, and who in turn had a direct connection to a lineage of traditional Yoga teachers.

When I was involved in the Yoga Society at Monash University in the 1970s, we would periodically borrow this film from the State Film Library for screening.

After numerous showings, the State Film Library copy of the film was no longer in mint condition and circa 1977 it was decided that the Yoga Education Centre should have its own print of the film.

I was asked to arrange a new print. From memory, John Murray was overseas at the time and we were directed to his son Scott, then editor of “Cinema Papers”, to arrange the print, the only proviso being that the request had Vijay’s approval (which it did). Subsequently a new 16mm print was struck, and this copy became the one used for screenings at the Yoga Education Centre and the university Yoga societies.

Vijayadev and Jill Yogendra re-located to rural Queensland in 1981, establishing a new primary campus for the School of Total Education, which Vijay had founded in Melbourne in 1977. The Yoga Education Centre in Melbourne closed its doors in the mid-1980s.

Over the intervening years I often recalled the film and wondered if some day it could be resurrected for a new audience. This eventually led me, about ten years ago, to making enquiries with the state film libraries.

Both ACMI (successor to the State Film Library) in Melbourne and the State Library of NSW in Sydney confirmed that they held copies of the film, available for viewing on-site, but no longer offered for loan.

The next question was whether John Murray was still alive and could be contacted. I discovered that he had a company, Murray Mancha Pty Ltd, and a website, where Yoga and the Individual was mentioned. My attempts to make contact via letter did not yield any results (although I subsequently discovered that John did reply to my letter, but for some reason I did not receive the reply).

It seemed as though these enquiries had reached a dead end. Then, out of the blue in July 2019, Malcolm Richards from Cameraquip in Melbourne told me that John Murray had been to Cameraquip recently to have his films scanned.

Through Malcolm I was able to get John Murray’s phone number and subsequently called him and was able to find out more about the film’s history and John’s intentions for it and his other works.

Here is a brief summary of the parts of the conversation with John Murray that are relevant to “Yoga and the Individual”:

-

John initiated the film. After working at the ABC, he went out on his own and worked in various jobs to pay for filming it. He wanted to prove to Australian filmmakers that films with high visual and sound quality can be done in Australia.

-

In making the film, John wanted to correct misconceptions about Yoga, and especially to emphasize the metaphysical part, which is the subject of the prologue of the film. He wanted the film to create an atmosphere to express these ideas. John went to various ashrams in India, including the Shri Aurobindo ashram at Pondicherry.

-

John had to work out how to show the Yoga asanas without distracting with a set. He wanted to contrast the stillness of the figures and the way they were moving.

-

The film was shot in 1964/65 at the old Artransa studio in High Street Kew (Melbourne) which had a platform or stage with a polished wooden floor about a foot above floor level. He used an ACS (Australian Cinematographers Society) cameraman who shot it on 35mm.

-

John chose the film’s title and wrote the narration. The Indian music was done for the film by Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, also recorded in the Artransa studio.

-

John still has the materials but has not found the original 35mm elements yet. Malcolm Richards at Cameraquip has scanned a beautiful black and white 16mm copy which John had kept and was in mint condition.

-

John’s intentions are that he would like this film and his other films to be publicly available. Initially he was thinking of DVDs, but DVDs have gone out of fashion. He is thinking about putting the film online (e.g. Vimeo). He has not yet made a decision to do that.

As a follow up to this conversation, John provided additional information conveyed to me in an email from his daughter Sue, including:

-

Filming of the Yoga practices was completed in one day.

-

John engaged Vijay and Jill Yogendra to perform postures in the film and to posit Hatha Yoga in recreating the overall picture of what particularly Westerners knew of Yoga.

-

John registered the film with the relevant Commonwealth department in February 1966 to confirm his copyright in the film.

In September 2020 Malcolm Richards informed me that John Murray had passed away earlier that year.

Addendum #2: Scanning and Restoration

The discovery that John Murray had arranged for a good quality original print of Yoga and the Individual to be scanned by Cameraquip in May 2019 was a breakthrough which led to my being able to assist with the restoration of this film.

Sue Murray provided me with a copy of the original scan file in April 2023.

The misfit soundtrack

On inspecting the scan, it turned out that there was something not quite right about it. This took a little detective work to solve.

I was familiar with this film from having seen it multiple times in the 1970s.

What was strange about the new scan was that the soundtrack did not seem to match the visuals. I remembered how the narration and music synced with particular edits and which parts of the narration pertained to particular visuals.

Additionally, the narrator’s voice did not sound as I remembered it. The pitch was too high.

Moving the soundtrack forwards or backwards relative to the picture fixed the correlation in some places but broke it in others. No positioning of the soundtrack would fit the picture throughout the film. The soundtrack scan appeared to be shorter than the picture scan.

I guessed that maybe the soundtrack had been scanned at a different speed from the picture. Either the picture and soundtrack had been on separate reels scanned at different speeds, or a composite print was scanned in two passes at different speeds. Malcolm Richards at Cameraquip confirmed it was possible the sound and picture were scanned separately.

So I did a quick stretch of the soundtrack to the same length as the visuals. The slowdown factor was 0.96, which of course is exactly 24/25. After that it synced perfectly.

This suggested that the picture was scanned at 24fps while the soundtrack was scanned at 25fps, thus making it shorter in duration.

To fix it properly, I extracted the soundtrack audio, re-stretched and re-sampled it using iZotope RX (for the best quality result) and re-synced that soundtrack to the visuals.

After that the narration fitted the visuals as it should.

This scan of the 16mm optical soundtrack also suffered from what could be called “modulation noise”. Neither the Dialog Isolate or Voice Denoise filters in iZotope RX removed this noise in a satisfactory way. In the end, the Voice Isolation filter in Final Cut Pro X worked better to reduce the intensity of noise and hiss. After that I added a little treble boost to brighten it up. (Perhaps there is a more original soundtrack element — 35mm or magnetic film — among the materials John Murray mentioned to me as yet to be found.)

With the soundtrack problems fixed, it was time to examine the picture scan.

The Cameraquip scan

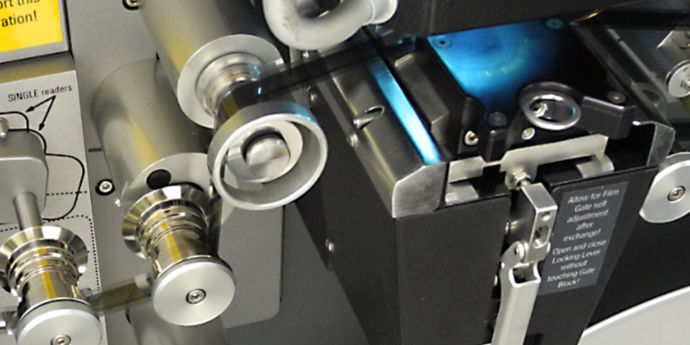

It is worth noting that Cameraquip scanned the film using a Golden Eye scanner from Digital Vision. This is a professional quality “line scanner” which produces excellent results.

Cameraquip also ran the picture scan through Digital Vision Loki software which does:

-

Automated frame stabilisation (to reduce jitter introduced in the original camera-to-final-print workflow).

-

Removal of some dust artefacts.

The stabilisation is quite effective, but the dust removal (at least in this grade of automated software) is not perfect. Nevertheless, for a 16mm print, the result is quite satisfactory.

Cropping and resolution

The Golden Eye scanner is a “2K” scanner. The full-resolution frame width is 2048 pixels. For the traditional 4/3 aspect ratio of 35mm and 16mm film, this corresponds to a frame height of 1536 pixels. This resolution is more than adequate to preserve all the detail in the 16mm print, which would have been a reduction print from the original 35mm elements.

The film had been scanned with some “overscan” — so that the (camera gate) frame edges were visible — and this needed to be cropped off.

I wanted to avoid re-sampling the frames if possible, since fractional re-sampling tends to reduce sharpness.

1080p resolution is 1920 x 1080 pixels with an aspect ratio of 16/9. For the same frame width (1920 pixels), the frame height for a 4/3 aspect ratio is 1440 pixels.

Cropping the frames from 2048 x 1556 to 1920 x 1440 pixels removed 128 pixels (6.25%) from the width and 116 pixels (7.5%) from the height. This was enough to crop off the rough frame edges and provide a clean frame border without sacrificing meaningful content. Importantly, no re-sampling was needed.

Grading adjustments

Cameraquip had done a basic grading of the scanned footage. On inspection it was clear there were shots which could benefit from additional grading. This was undertaken on a a shot by shot basis.

Another noticeable artefact was rapid tonal shifts in the first few frames after shot transitions. For example, on transitioning to a darker shot, it will be too dark initially, but gets lighter over 3–4 frames. A transition to a lighter shot will initially look over-exposed, then will darken over 3–4 frames. I doubt this would have come from the Cameraquip scanner. More likely it could be an artefact of some kind of auto-grading done in an optical printer or contact printer at the time the film was made.

These rapid tonal transitions were noticeable. Some experimentation showed they could be counteracted with keyframed grading adjustments to the offending shot transitions.

Also noticeable were dirty splices in some places. These were easily removed by replacing the dirty frame with a clean adjacent frame.

Tidying up

Finally, the Academy Leader (10..9..8…) at the start, and the blank film at the end were trimmed off, along with noisy “silent” soundtrack at the start and end.

New output files

Two new output files were generated using Prores 422 (30GB file) and H264 (2GB file) codecs.